We had followed the river down from Galena. In places it was much more stark and beautiful than the Midwest is supposed to be. We arrived at Hannibal in the mid-afternoon and decided to take a stroll down the riverfront. Around the corner from Mark Twain’s boyhood home an antique shop drew us inside. There I found a postcard from the Doncaster Racecourse in England, postmarked 1907. It was not a particularly interesting view, but after reading what was written upon it, I bought it.

Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain’s biographer, tells us that shortly after arriving in England in June 1907, Twain picked up the morning paper and read the headline, “Mark Twain Arrives: Ascot Cup Stolen.” The juxtaposition of the two items was likely an intentional attempt at British wit. A couple of weeks later, Twain attended a dinner held in his honor at the Savage Club, an institution that still exists and bills itself as “one of the leading Bohemian Gentleman’s Clubs in London.” There he was presented with a gilded plaster reproduction of the Ascot Cup along with a handwritten note from his supposed “accomplice” in the theft. During his speech, he did not mention the cup or the attempts at humor surrounding his implied involvement with its disappearance. He spoke instead of his friendship with Henry Morton Stanley, the famous African explorer and Confederate veteran of the Battle of Shiloh. Twain had been made an honorary life member of the club a decade earlier and Stanley was one of only three others who had also received this honor. The two other recipients were the Arctic explorer Fridtjof Nansen and King Edward VII, when he was still Prince of Wales. It was on this same trip that Twain was invited to Windsor Castle to attend a garden party hosted by King Edward and Queen Alexandra. There he famously upstaged the royal couple by grandly offering to buy the castle from them.

The Ascot Gold Cup had been stolen during the 4:30pm race at Ascot on 19 June. It was one of the biggest news stories of the season. King Edward himself had paid for its manufacture, imbuing it with a hint of the authority of royal sanction. Scotland Yard dispatched its best men on a quest to find the cup. They could only understand how such a theft could have occurred, in broad daylight and apparently under the watchful eyes of several guards, by creating a myth to explain it. The theft, according to them, was undoubtedly perpetrated by an organized band of gentleman thieves with access to motor cars. Later in the summer, a replacement was commissioned to be made by Garrard’s, the very firm that had supplied one of the guards employed to watch over the cup at Ascot. The search continued for months afterwards, but the original cup was never recovered.

In 1931, former Scotland Yard Special Branch detective Edwin T. Woodhall published an article claiming that a servant involved in the theft had, decades after the fact, confessed to him that it was carried out as the result of a wager between two members of the nobility in order to impress a third, a lady. The servant himself had carried out the theft. There was no organized band of gentleman thieves. The servant was simply ordered to steal the cup so that his employer could win the wager. He did so during an opportune moment when, the other guards having stepped away, the lone policeman on duty turned his back for a moment. The theft was meant as a joke and the intention had originally been to return the cup, but after the event received such widespread publicity the trio panicked. The servant told Woodhall that some time later in 1907 he accompanied his employer out to sea where the cup was placed in a weighted bag and dropped into the water. By the time of the article, the three nobles involved were long dead and the servant was in the process of immigrating to “the colonies” under a new name.

On the day the cup was stolen at Ascot, 19 June 1907, a man named John Henry Taylor who was sometimes known as D. J. W. Tremayne, was performing with a Commedia dell’Arte troupe there as a singing pierrot. As was customary, the King, himself an ardent fan of horse racing, was in attendance. He had also attended the Windsor races at which the troupe had performed earlier that summer. Taylor was a 25 year old diamond setter from London who had taken work as a singing clown that season “owing to business being at a standstill, and having practically nothing to do.” Later in the year, on 10 September, Taylor was tried for fraud at the Old Bailey in London.

The nature of Taylor’s crime and the trial itself are not exciting stuff. Before heading off to Windsor with the Commedia troupe, he convinced his employer, a jeweler, to allow him to take an assortment of jewelry worth over £1,000 to offer to clients whom he would likely meet there and at Ascot. His employer agreed, having no reason to distrust him. After arriving at Windsor, Taylor claimed to have met a Captain O’Shea, a man he assumed to be a wealthy regular customer of his father, a London hackney driver. This Captain O’Shea told Taylor that he had a foolproof betting system and convinced him to buy into it. Money was won at Windsor, lost at Ascot, and lost again after O’Shea convinced Taylor to pawn the jewelry in his possession. When Taylor didn’t arrive back at work with either the jewelry or the money to pay for it within a week or so after his expected date of return, a warrant was sworn out against him. On 12 September he was found guilty of fraud, but the question was left open as to whether this was due to actual criminal intent or through being duped by a “racing sharp.” As Pierrot in the Commedia dell’Arte was usually portrayed as a naif who was easily taken advantage of, the latter interpretation is the more poetic. His sentence is not recorded.

On 14 September, two days after Taylor’s trial ended, a letter from Alfred Nutt, renowned Celticist and president of the Folklore Society, was published in the journal The Academy. Nutt’s letter was in response to a series of three articles by Arthur Machen the journal had published the previous month. These articles outlined Machen’s theories on the pagan, pre-Christian origins of the legend of the Holy Grail, which he referred to as the Sangraal. Nutt, one of the era’s leading authorities on the Grail, did not refute Machen’s theories, but offered a respectful discussion of their finer points and addressed the weaker areas where questions might still remain. At least a half dozen books on the Grail were published in 1907 alone. Researchers such as Jessie Weston were actively delving ever deeper into the idea of pagan sources for the Arthurian legends in general and the Grail myth in particular. This line of thinking perhaps came to full fruition in her 1920 book From Ritual to Romance, which was cited by T. S. Eliot in his notes to The Waste Land and appears on Colonel Kurtz’s bookshelf in the film Apocalypse Now. Nutt pointed out that Machen had earlier stated that “we have had treatises to show that Adonis is somehow concerned in the story of the Sangraal” and wondered whether this could be evidence that Machen had foreknowledge of Weston’s as yet unpublished article “The Grail and the Rites of Adonis,” which appeared later in the year. The summer of 1907 was a particularly active season in what was overall a fertile period for Grail studies.

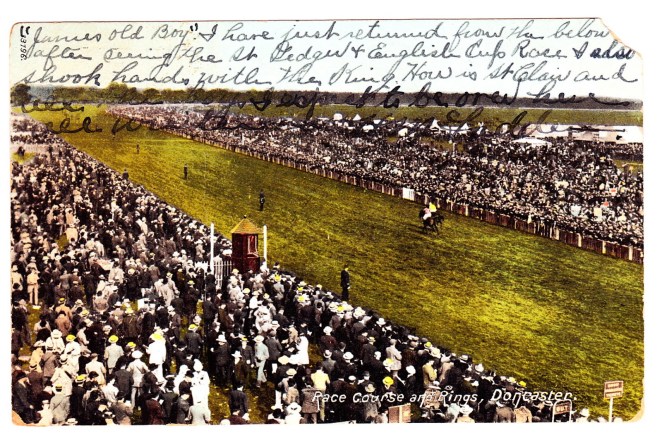

On 11 September 1907, a three-year-old stallion named Wool Winder won the St. Leger Stakes at Doncaster. Also on that date at Doncaster, a man named Ladden picked up a picture postcard to send to a friend in America. A century later, this card eventually found its way into the antique shop in Mark Twain’s hometown of Hannibal, Missouri, and now sits on my desk. On the front is a view from the grandstand at the Doncaster racecourse, looking down onto the finish line. The turf cuts at an angle across the picture plane. At the line are two riders nearly neck in neck, one slightly behind. On 13 September, Ladden wrote across the face of the card:

“James old boy,” I have just returned from the below after seeing the St. Ledger [sic] and English Cup Race. I also shook hands with the King. How is St. Clair and all the boys? I expect to be over here all winter. [H. M.?] Ladden.

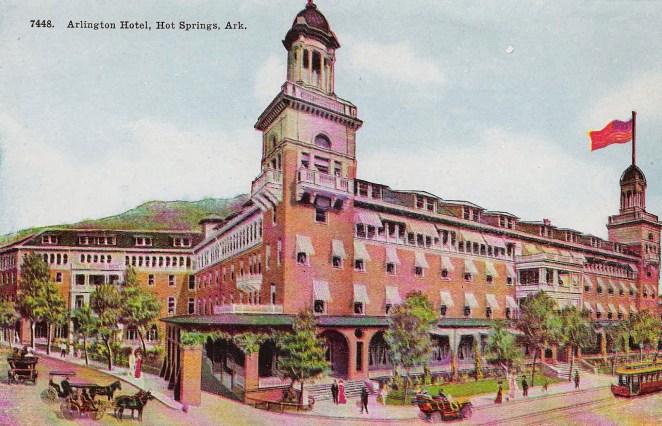

The card was addressed to Mr. James Cameron at the Arlington Hotel in Hot Springs, Arkansas. It was postmarked at Liverpool on 14 September and again at Hot Springs on 27 September. We can only make guesses as to the identities and ultimate fates of Messrs. Ladden and Cameron. With nothing to go on besides a relatively common name, Cameron will likely remain a mystery. H. M. Ladden’s sole appearance in the historical record is in a 1919 issue of Variety that mentions an individual of that name contributing fifty cents to a benefit fund for the vaudeville performer Bert Leslie. The tantalizing idea that he might himself have been a vaudevillian is not borne out by research. Wool Winder’s fate is known, however. He was sold to the Austrian government in 1909 and spent the war years as an enemy thoroughbred.

The Arlington Hotel in 1907 was a grand building of 300 rooms that had been built in 1893 as a replacement for the original 1875 structure. The hotel served the nearby Hot Springs National Park with its famous hot mineral baths, then believed to relieve diseases of the skin, blood, nerves, and the “various diseases of women.” In its small way Hot Springs, Arkansas, was a North American version of Bath in England or Baden-Baden in Germany, where people of means would retire for a few weeks to “take the waters.” We can only guess at what Cameron was doing there, but there is a hint. Oaklawn Park Racetrack had opened at Hot Springs in 1905. The track featured six races a day on the British model. As Cameron’s friend Ladden was a racing enthusiast, it’s easy to draw the conclusion that they were both “sports” and were in their respective locales that summer to enjoy the horse racing. Due to a literally titled bill introduced into the Arkansas state legislature, “An Act to Prevent Betting in any Manner in This State on any Horse Race,” which had just passed into law in February, the 1907 racing season was to be the last at Oaklawn Park for a decade.

Both Bede and Geoffrey of Monmouth wrote of the legend of Hengist and Horsa, whose names respectively mean “stallion” and “horse.” These heroes arrived in Britain in the 5th century as mercenaries under the employ of Vortigern, King of the Britons. The Anglo-Saxon invasion has traditionally been dated to the appearance of these horse-men upon England’s shores. Multiple earlier sources mention pairs of twin brothers associated with the horse appearing throughout Germanic folklore. The archaeologist J. P. Mallory has linked these with other divine horse twins in early Indo-European sources, such as Castor and Pollux in Greece or the Ashvins of the Vedas. From the beginning, what were to become English language and culture emerged with a very strong association with the horse .

In many of the Grail legends, the cup gets its power from the fact that it was used, touched, by Jesus during the Last Supper. The Royal Touch imbues it with authority. In his Idylls of the King, Tennyson casts those seeking the Holy Grail as being on a noble quest, one worthy of such an object. Arthur and his knights represent the societal ideal; and the implication is that it is only natural that the Grail belongs with them, an embodiment of Victorian virtue. The horse occupies a darker space in Tennyson’s view. He associates it with the savage, the pagan, when referring to the twelve legendary battles fought by Arthur, possibly against the Germanic forces of Hengist and Horsa: “Knights that in twelve great battles splashed and dyed / The strong White Horse in his own heathen blood.” The horsemen bring disorder and chaos. These heathen horsemen interrupt the search for the Grail with their constant warring. Why do Arthur and his knights spend so much energy searching for the Grail? What is missing from their world that can only be made whole by finding this sacred cup?

We are left with a postcard, a fountain pen scrawl of ink across its face, and a handful of names of men all now long dead. I had to use a jeweler’s loupe to make out the signature on the card. Even magnified, I’m not entirely certain of the first two initials. The signature itself becomes an act of mystery. Below the signature and the message that tells us its author received the Royal Touch, thousands watch two riders, tiny in this landscape, crossing a barren expanse of turf. Was Ladden also at Windsor and Ascot that summer? Did he see Taylor perform as Pierrot? Did he witness the commotion on the afternoon of 19 June when it was discovered that the Ascot Gold Cup was missing and then chuckle, along with Mark Twain, at the next morning’s headline? Did he see the Scotland Yard men assembling to begin their quest, while the thunder of hoofbeats echoed in the background?

—Stephen Canner